Introduction

In the world of manufacturing, injection molding remains the gold standard for producing consistent, high-quality plastic parts. However, the biggest barrier to entry isn’t usually the cost of the plastic resin—it’s the cost of the mold (or “tool”) itself.

For product designers and engineers, the “tooling strategy” is often the most critical decision in the project lifecycle. Making the wrong choice can lead to thousands of dollars in wasted budget or, conversely, a mold that wears out before you fulfill your orders.

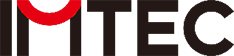

The industry generally divides mold making into two categories: Soft Tooling and Hard Tooling. While the names imply a difference in physical texture, the distinction actually lies in the mold material’s metallurgy, machining speed, and longevity.

This guide explores the technical and commercial differences between these two approaches to help you decide which path aligns with your budget, timeline, and production volume.

What is Soft Tooling?

Soft tooling generally refers to molds machined from materials that are softer and easier to cut than traditional tool steel. It is the dominant method for prototyping, bridge production, and low-volume manufacturing runs (typically 50 to 5,000 parts).

It is important to clarify that “soft” does not mean the mold is pliable like rubber. It is almost always made of metal, but metal that lacks the extreme hardness of heat-treated steel.

Common Materials

- Aluminum Alloys: The most common material for soft tooling is aluminum. High-grade alloys like Aluminum 7075 or QC-10 are frequently used because they offer high strength and excellent machinability.

- Mild Steels: Occasionally, lower-grade, non-hardened steels are used for soft tooling, though aluminum is preferred for its cooling properties.

- 3D Printed Composites: In very specific, ultra-low volume cases, 3D printed polymer molds are used, though they degrade very quickly.

Advantages of Soft Tooling

- Lower Initial Cost: Aluminum is much easier to machine than steel. It creates less wear on CNC cutters and can be machined at much higher speeds. This can reduce initial tooling costs by 30% to 50% compared to hard tooling.

- Faster Lead Times: Because the material is softer and requires no post-machining heat treatment, soft tools can often be ready in 1–2 weeks, compared to 4–8 weeks for hard tools.

- Superior Thermal Conductivity: This is a technical advantage often overlooked. Aluminum transfers heat 5x faster than tool steel. This allows the plastic to cool and solidify faster, significantly reducing cycle times and potentially lowering the part price.

- Ease of Modification: If a design change is needed, it is easier to machine away existing aluminum to open up a dimension than it is to modify hardened steel.

Disadvantages of Soft Tooling

- Limited Tool Life: Aluminum is susceptible to erosion from glass-filled plastics and wear from the clamping force of the machine. Soft tools typically last for 1,000 to 10,000 cycles before dimensions start to drift or flash (excess plastic) appears.

- Surface Finish Limitations: Soft tooling cannot maintain a high-gloss “mirror” polish (SPI A-1 or A-2). The metal is too soft and will scratch during part ejection. It is better suited for matte or textured finishes.

- Fragile Parting Lines: The edges where the two halves of the mold meet can round over or dent easily, leading to cosmetic defects on the part.

What is Hard Tooling?

Hard tooling creates the workhorses of the manufacturing world. These molds are machined from high-grade steel capable of withstanding millions of cycles, high temperatures, and abrasive materials. This is the standard for mass production.

Common Materials

- P20 Steel: A pre-hardened tool steel often used for “Class 102” molds. It is durable but not as brittle as fully hardened steel.

- H13 Steel: The industry standard for high-volume production. It is heat-treated to extreme hardness (Rockwell C 48-52) to resist wear and thermal fatigue.

- Stainless Steel (420): Used when corrosion resistance is needed, such as when molding PVC or other corrosive plastics.

Advantages of Hard Tooling

- High Volume Durability: A properly maintained H13 steel tool can run for 1 million+ cycles without significant wear.

- Tight Tolerances: Hard steel is rigid and does not deform under the high injection pressures required for complex parts. This allows for extremely tight dimensional accuracy.

- Superior Surface Finishes: Hard tooling is required for high-gloss, optical-grade finishes. The steel is hard enough to be polished to a mirror shine without scratching.

- Complex Actions: Hard tooling is better suited for complex side-actions, sliders, and lifters that are required for parts with undercuts.

Disadvantages of Hard Tooling

- High Initial Investment: The raw material is expensive, and machining hardened steel often requires EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining) and slow CNC cutting speeds. Costs are significantly higher than soft tooling.

- Long Lead Times: Between rough machining, stress relieving, heat treatment, and final grinding/polishing, hard tooling often takes 4 to 12 weeks to complete.

- Difficult to Modify: Once a steel tool is hardened, making changes is difficult. It often requires welding and re-grinding, which leaves “witness marks” on the tool and can be expensive.

Quick Summary: The Trade-Off

| Feature | Soft Tooling (Aluminum) | Hard Tooling (Steel) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Speed & Low Cost | Longevity & Precision |

| Typical Volume | 50 – 5,000 parts | 100,000 – 1,000,000+ parts |

| Lead Time | Days to Weeks | Weeks to Months |

| Heat Transfer | Excellent (Fast cycles) | Moderate (Standard cycles) |

Key Differences: A Deep Dive

While the definitions above outline the general pros and cons, understanding the nuanced differences is crucial for making an informed manufacturing decision.

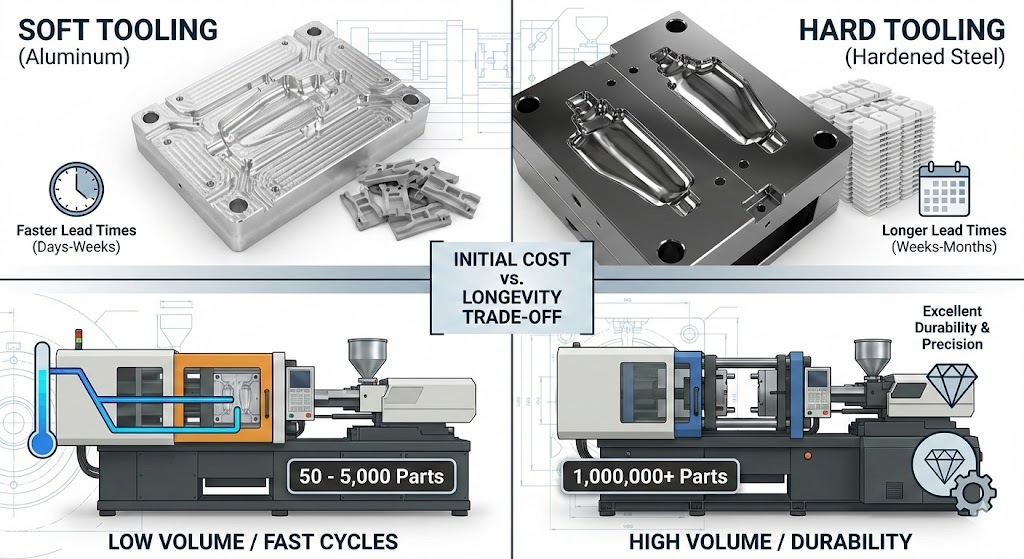

1. Cost Dynamics and the “MUD” Strategy

The most obvious difference is initial cost. Soft tooling is significantly cheaper because aluminum machines faster and requires no post-machining heat treatment. Hard tooling involves expensive steel alloys, slower machining speeds, and often complex Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) processes to burn features into hardened metal.

However, cost is not always binary. A common middle ground used in the industry is the Master Unit Die (MUD) system.

- The Strategy: A molder uses a universal, reusable steel mold base (frame) that stays in the machine. They only machine smaller “inserts” (the core and cavity that shape your specific part) out of soft steel or aluminum.

- The Benefit: You avoid paying for the heavy steel base structure, significantly lowering the entry cost for prototyping or bridge tooling while still utilizing standard molding machinery.

2. Cycle Time and Thermal Conductivity

This is often the most overlooked differentiator. The speed at which you can produce a part depends largely on how fast you can cool the molten plastic.

- Soft Tooling Advantage: Aluminum has significantly higher thermal conductivity than steel. It pulls heat out of the plastic much faster, allowing the part to solidify quicker. For a production run of 5,000 parts, the faster cycle time of an aluminum tool can sometimes offset its higher initial cost compared to a very cheap steel tool.

- Hard Tooling Reality: Steel holds heat longer. To achieve fast cycle times with hard tooling, complex, drilled internal cooling channels (“conformal cooling”) are often required, further increasing tooling costs.

3. Surface Finish and Accuracy

If your part requires a mirror-like, optical finish (SPI A-1 or A-2), hard tooling is mandatory.

- Aluminum is too soft to hold a high polish for long; the ejection phase of the molding cycle will microscopically scratch the surface after a few hundred shots, degrading the glossy finish.

- Hardened steel is resilient enough to maintain a flawless polish for hundreds of thousands of cycles.

Similarly, for parts requiring extremely tight tolerances (e.g., ±0.001 inches), hard steel is preferred because it will not deflect or flex under high injection pressures, ensuring consistent part dimensions.

4. Material Compatibility (Abrasiveness)

The plastic resin you choose dictates the tool you need. Standard plastics like Polypropylene (PP) or ABS are relatively gentle on a mold.

However, engineering-grade resins often contain additives like glass fibers or mineral fillers for added strength. These materials act like liquid sandpaper inside the mold. Glass-filled nylon injected into an aluminum soft tool will erode the gate and surface details rapidly, destroying the tool in under 1,000 shots. Hardened H13 steel is required to resist this abrasion.

Ideal Applications

Choosing the right tooling strategy depends entirely on where you are in your product development lifecycle.

Best Applications for Soft Tooling (Aluminum/Mild Steel)

- Prototyping and Design Validation: When you need 50–200 parts in the actual production material to test fit, form, and function before committing to expensive steel tools.

- Market Testing: Producing a small batch to gauge consumer interest at a trade show or for a limited beta release.

- Bridge Tooling: A critical strategy where a soft tool is built quickly to start supplying parts immediately while waiting for the long lead time of a high-volume hard tool being built elsewhere.

- Low-Volume Niche Products: Products with a total lifetime demand of under 5,000 units where the investment in hard tooling will never pay off.

Best Applications for Hard Tooling (Hardened Steel)

- High-Volume Mass Production: Any project requiring 100,000 to millions of parts annually (e.g., consumer electronics, automotive components, bottle caps).

- Abrasive Materials: Parts made from glass-filled or mineral-filled resins that would chew up soft tooling.

- High Precision Requirements: Gears, medical devices, or electronic connectors where dimensional stability across millions of cycles is critical.

- High Cosmetic Requirements: Parts requiring a lasting high-gloss finish or intricate, consistent texturing.

Factors to Consider When Choosing

When facing the soft vs. hard tooling decision, evaluate your project against these five critical factors.

1. Total Production Volume (Lifetime)

This is the primary filter. If your lifetime forecast is under 5,000 parts, start by looking at soft tooling. If it’s over 50,000, hard tooling is almost certainly the correct path. The gray area in between requires a deeper cost analysis.

2. Speed to Market (Lead Time)

Do you need parts in 3 weeks to meet a critical launch deadline, or do you have 3 months? If speed is paramount, soft tooling is the only option that can deliver quickly. Hard tooling is a slow, deliberate process.

3. Budget Constraints (Capex vs. Opex)

Are you constrained by initial capital expenditure (Capex)? Soft tooling lowers the upfront sticker price. However, if you have the capital, hard tooling offers a lower piece-price over the long term, reducing operational expenditure (Opex).

4. Part Geometry and Complexity

While both methods can handle complex geometry, hard tooling is better suited for intricate “actions” inside the mold, such as complex sliders, lifters for undercuts, and unscrewing mechanisms for threaded parts. These moving components wear out quickly if made from soft metal.

5. The Resin Material

As mentioned above, if your Bill of Materials calls for 30% glass-filled Nylon, you must budget for hard tooling, regardless of your volume. Using soft tooling for abrasive materials is false economy.

Cost Analysis: Soft vs. Hard Tooling

The decision often comes down to a math problem: Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). You must balance the upfront “sticker price” of the mold against the long-term “piece price” of the part.

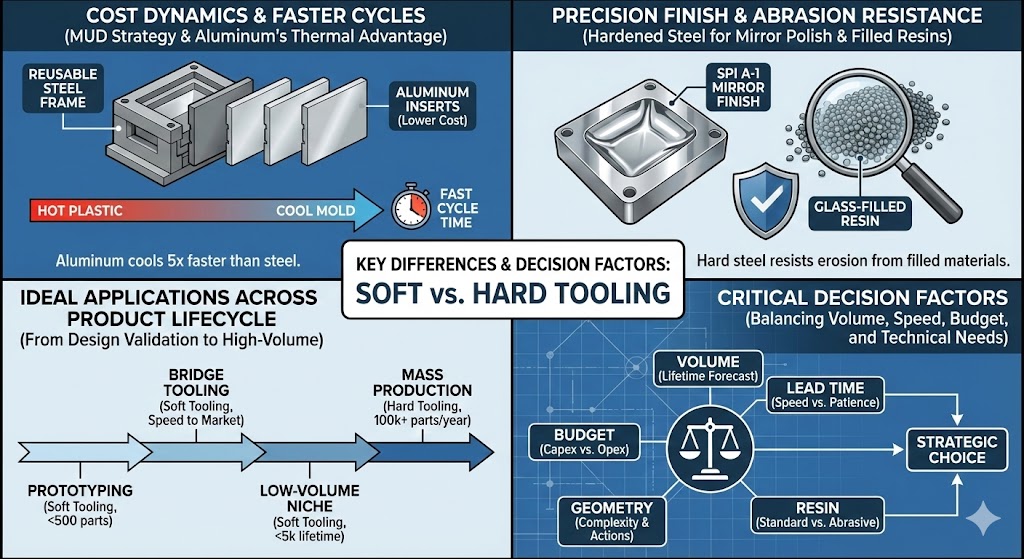

1. The “MUD Frame” Strategy (Pro Tip)

Before looking at the full cost, you should know about Master Unit Die (MUD) inserts.

Instead of buying a full custom mold base (which is heavy and expensive), you can use a “MUD Insert.” This is a standard frame owned by the molder, into which they slide your specific core and cavity.

- Cost Impact: This can reduce your initial tooling cost by up to 66% because you aren’t paying for the structural mold base, only the shaping area.

- Best For: Both soft and hard tooling strategies for parts under 6 inches in size.

2. Hypothetical Breakdown: “The Plastic Housing”

Let’s look at a real-world scenario for a standard plastic housing (approx. 4" x 4") to see where the break-even point lies.

| Cost Variable | Soft Tooling (Aluminum 7075) | Hard Tooling (P20/H13 Steel) |

|---|---|---|

| Tooling Investment | $3,500 | $12,000 |

| Est. Tool Life | 5,000 shots | 250,000+ shots |

| Cycle Time | 20 seconds (Fast cooling) | 35 seconds (Standard cooling) |

| Part Price | $1.20 | $1.45 (at low vol) / $0.85 (at high vol) |

The Break-Even Analysis:

-

At 1,000 units:

- Soft Tooling Total: $3,500 + ($1.20 * 1,000) = $4,700

- Hard Tooling Total: $12,000 + ($1.45 * 1,000) = $13,450

- Winner: Soft Tooling by a landslide.

-

At 20,000 units:

- Soft Tooling Total: Requires 4 new molds ($14,000) + Parts ($24,000) = $38,000

- Hard Tooling Total: One mold ($12,000) + Parts ($17,000 @ bulk rate) = $29,000

- Winner: Hard Tooling.

The Lesson: The “crossover point” usually happens between 5,000 and 10,000 units. If you plan to scale beyond that, the expensive steel tool becomes the cheaper option.

Future Trends in Injection Molding Tooling

The binary choice between “aluminum vs. steel” is blurring as technology advances. Here is what is changing the game in 2025 and beyond.

1. Conformal Cooling (The “Internal Veins”)

Traditionally, cooling channels are drilled in straight lines through the steel. This leaves “hot spots” where the drill cannot reach.

- The Innovation: Using Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) (3D metal printing), engineers can print a steel mold with cooling channels that curve and twist inside the mold wall, perfectly following the shape of the part.

- The Benefit: This reduces cycle times by 20% to 40% and virtually eliminates warping.

2. Hybrid Tooling

Designers are increasingly using hybrid molds. They use a standard machined steel base for durability but use 3D-printed steel inserts for complex features that would be impossible to machine with a CNC cutter. This blends the precision of AM (Additive Manufacturing) with the durability of traditional tooling.

3. Smart Molds (Industry 4.0)

High-end hard tooling is now being equipped with embedded piezoelectric sensors. These sensors monitor pressure and temperature inside the cavity in real-time, automatically adjusting the injection molding machine to prevent defects before they happen.

Conclusion

Choosing between Soft and Hard tooling is not about “good vs. bad”—it is about risk management.

- Choose Soft Tooling (Aluminum) if: You are in the prototyping phase, need parts in under 2 weeks, have a strict budget under $5k, or your total market demand is uncertain. It is the agile, low-risk entry point.

- Choose Hard Tooling (Steel) if: You have a validated design, require optical-grade finishes, are molding abrasive glass-filled materials, or need to guarantee supply for hundreds of thousands of units. It is the investment in stability and quality.

Final Recommendation:

If you are unsure, ask your manufacturing partner about a “Bridge Tooling” strategy. Start with a low-cost aluminum tool to get to market quickly. Use the revenue from those first 5,000 parts to fund the construction of the permanent P20 steel mold. This gives you the speed of soft tooling with the eventual longevity of hard tooling.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Can I convert a soft tool into a hard tool later?

A: No. You cannot “harden” an aluminum mold into steel. However, if you use a MUD (Master Unit Die) system, you can swap out the aluminum core/cavity inserts for steel ones while keeping the original mold base frame, which saves money.

Q: Is soft tooling always cheaper than hard tooling?

A: Generally, yes. Soft tooling is usually 30-50% cheaper upfront. However, if your production volume exceeds 10,000 units, the cost of replacing worn-out soft molds will eventually make it more expensive than investing in one durable hard mold.

Q: Can I use soft tooling for glass-filled nylon?

A: It is not recommended. Glass fibers are abrasive and will scrub away the details of an aluminum mold very quickly. If you must use soft tooling for abrasive materials, expect a very short tool life (often under 500 parts).

Q: What is the lead time difference?

A: Soft tooling can often be machined and ready for the first shot (T1) in 1-2 weeks. Hard tooling typically requires 4-8 weeks due to heat treatment, EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining), and polishing time.

Q: Does the tooling material affect the plastic part quality?

A: In terms of dimensions, no—both can produce accurate parts. However, in terms of finish, hard tooling is required for high-gloss, optical-clear finishes. Soft tooling is better suited for matte or textured finishes.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Cavity: The concave side of the mold that forms the outer surface of the part (often called the “A-side”).

- Core: The convex side of the mold that forms the inner surface and structural details (often called the “B-side”).

- EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining): A process used in hard tooling where a charged electrode burns a shape into hardened steel that cannot be cut by traditional drills.

- Flash: Defect where excess plastic leaks out of the mold parting line. This happens frequently as soft tooling begins to wear out.

- Heat Treatment: The process of heating and cooling steel to alter its physical properties, making it harder and more durable (essential for hard tooling).

- Shot: A single cycle of the injection molding machine.

- T1: The “Test 1” samples—the very first parts produced by a new mold to verify the design.

English

English bahasa Indonesia

bahasa Indonesia